Entry points to science fiction literature (Evan's Guide to SF - Part 1)

Been craving some space opera, cyberpunk, or anything in between? Look no further!

Welcome back to The Science Fictional Now!

Over the past few years, I’ve frequently been asked for science fiction book recommendations, and all too frequently I haven’t been prepared to give a helpful answer off the top of my head. That all ends with this guide, which will solve as a public living resource dedicated to helping people find starting points for science fiction. Because everyone has slightly different taste and because there are wonderful works of science fiction not suited to individuals unfamiliar with the genre, I’ve opted to create a dedicated list of “gateway” works rather than a simple list of favorites (stay tuned for that though!). That doesn’t mean that I’ve compromised on quality, however; I would still recommend all the stories on this list to seasoned SF1 readers.

The bulk of the recommendations are sorted into categories based on other genres with which they share similarities or directly overlap. I’ve included both novels and shorter works in most categories to offer options for readers with different goals and time constraints. I’ve also provided a “history” list for those interested in reading SF from a particular time period, as well as a short list of books that I don’t recommend starting with.

This post is the first in a series that I plan to write about science fiction, with the overall goal of demystifying the genre and consolidating some key information about it. In the future, I hope to write an overview of science fiction’s history, publish a list of my favorite works across different media, and discuss the genre’s scope as well as some key ideas and relevant terminology. After publication, these will all be updated periodically to maintain maximum relevance and accuracy. Please feel free to offer feedback on this list, either by commenting below or reaching out directly.

A few final notes before I dive into the list:

I have not read every piece of science fiction ever published. There are undoubtedly great intro stories missing from this list simply because I haven’t read them. If nothing catches your eye right away, try checking back in a few weeks or months.

These recommendations are based on my personal taste. I’ve done my best to include something for everyone here, but at the end of the day it’s still SF filtered through my eyes. There are canonical works within the genre that I just don’t like well enough to recommend, and it’s possible that great intro points for you might be excluded for that reason.

Different people have different definitions of science fiction. I think that nearly all the stories on I’ve included here fall squarely within conventional definitions of the genre, but know that my personal tendency is to define SF pretty inclusively. If a story describes a new technology based in real-world science, I’d call it science fiction. If a story has the aesthetics of science fiction (space ships, aliens, etc.) but little accompanying technical detail, I’d personally still call it SF without hesitation.

I don’t want to spoil these books. The plot summaries and cursory analyses I’ve provided here are intended only to whet your literary appetite. After all, my goal is to convince you to go read some great SF!

Table of Contents

If you like…

Science fiction movies

“The Minority Report” - Philip K. Dick (1956)

In a futuristic New York, John Anderton is the head of Precrime, a division of the NYPD that predicts and stops all crime before it can happen. When Anderton receives a report the he himself will commit a murder within the next week, he goes on the run, convinced that a conspiracy is at hand. “The Minority Report” showcases Dick’s ability to spin a riveting yarn while also foreshadowing the more introspective, philosophical style that would come to define his novels. Inspired in part by Dick’s concerns about the Cold War, the novella explores his suspicion of authoritarianism alongside questions of causality and free will. While I prefer Dick’s original version, a loose film adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg was released in 2002.

Mickey7 - Edward Ashton (2022)

Mickey Barnes lives in a beachhead colony on the frozen planet of Nilfheim, where he works as as “expendable”. It’s Mickey’s job to take on the most dangerous tasks required for the colony’s survival; should he perish, he can be “resurrected” by having his memories transferred to a clone. As the planet’s native fauna become increasingly aggressive, a malfunction results in the creation of two living Mickeys. Mickey7 is a novel that does a number of things well: its high-concept premise has some interesting philosophical implications, but it’s also a very down-to-Earth novel with several likable but imperfect characters, lots of humor, and good science. A movie adaptation helmed by Parasite director Bong Joon-ho is slated for release next April.

Fantasy

“Tower of Babylon” - Ted Chiang (1990)

One need only look to Star Wars to find a fusion of science fiction and fantasy, with magic and spirituality set against a technologically-advanced interstellar background. Ted Chiang’s debut novelette takes a slightly different approach to “science fantasy” by describing a secondary world that operates rationally, but according to the laws of Hebrew cosmology.2 The story follows construction worker Hillalum as he ascends the newly-completed Tower of Babel, hoping to enter the heavens once reaching the top. The story generates intrigue by exploring the intricacies of its world’s physics alongside the social dynamics of the tower residents that Hillalum meets on his journey. Ultimately, it explores questions about the relationship between religion and rationality, a theme that Chiang has returned to in subsequent stories.

Meru - S.B. Divya (2023)

Hundreds of years in the future, humanity lives alongside a genetically engineered post-human race called the alloys. While the alloy biology allows them to freely travel space, humans are legally confined to Earth on account of past ethical transgressions. Jayanthi, a human raised on Earth by adoptive alloy parents, is granted an exception to determine whether humans can survive on the newly-discovered planet Meru. Eager to ameliorate her species’ reputation, she travels to the planet with a young alloy named Vaha, only to find that powerful forces from her own side of the solar system oppose their mission. While Meru fits cleanly into the science fiction genre, fantasy readers will feel immediately at home due to the novel’s strong characterization, romantic elements, and mythological undertones (the story is loosely adapted from a section of the Mahabharata).

Horror

“The Screwfly Solution” - Raccoona Sheldon (1977); link

Alan, an American entomologist working in Colombia, exchanges letters with his wife Anne during an outbreak of femicide. While male chauvinist groups emerge to supply misogynistic justifications for the wave of murders, no organized female resistance is formed. As the epidemic reaches fever pitch, lan and Anne put the pieces together, realizing that something even more sinister is at play. Alice Sheldon (here, writing under the pen name Raccoona Sheldon) frequently explored concepts related to human sexuality; its link to violent behavior is the primary source of fear in “The Screwfly Solution”. The dire atmosphere of the story is further accentuated by its epistolary format and the psychological reality of its central characters.

My Soul To Keep - Tananarive Due (1997)

Jessica, a journalist, enjoys a seemingly impeccable marriage to David, a Spanish professor. But unbeknownst to Jessica, her husband is immortal, born hundreds of years ago in Ethiopia. When friends and family begin dying around her, Jessica begins to suspect that David is hiding something, and his intricate web of secrets begins to come apart. My Soul to Keep is a page-turner that packs a real emotional punch, blending science fiction seamlessly with horror and mystery. At the core of the novel are questions about trust and the difficulty of truly understanding another person.

Literary fiction

“The Machine Stops” - E.M. Forster (1909); link

Forced to abandon the Earth’s surface, humans now live underground in isolated rooms where their every needs are met by an all-encompassing Machine. Humanity’s reliance on the Machine has turned it into an object of worship. While Vashti, a middle-aged woman, accepts this way of life without question, her rebellious son Kuno is a determined to dismantle the system that controls their world. English literary icon E.M. Forster published “The Machine Stops” the year after his acclaimed novel A Room with a View. The story stands as an early warning about human over-dependence on technology, exploring how it might precipitate an unnoticed slide into authoritarian rule.

Sea of Tranquility - Emily St. John Mandel (2022)

Spanning several settings, from early 20th-century Canada to a 25th-century Moon colony, Emily St. John Mandel’s Sea of Tranquility follows several characters who all have chance encounters with a spatiotemporal anomaly. These experiences lead the characters to question not only aspects of their own identities, but their ability to perceive fundamental reality. Mandel weaves the disparate settings together through a thoughtfully-crafted narrative structure. Literary-minded readers will also appreciate the lucid prose and metaphysical themes contained in the novel.

Crime fiction

“Murder by Pixel: Crime and Responsibility in the Digital Darkness” - S.L Huang (2022); link

S.L. Huang’s short story about “Sylvie”, a chatbot who cyberbullies multiple people into committing suicide, reads like a true crime podcast written by techno thriller fans. The story is replete with factual research, which Huang’s narrative manages to give stakes while leaning away from true crime’s most lurid characteristics. Any sense of morbid fasciation is in the service of the story’s goal of forcing readers to contend with the rapid pace of AI advancement in the light of existing online social dynamics.

Futureland - Walter Mosley (2001)

All of the stories in Easy Rawlins writer Walter Mosley’s cyberpunk short fiction anthology have crime fiction in their DNA, but it comes through the most clearly in two particular yarns. In “The Electric Eye”, private eye Folio Johnson is hired to investigate the deaths of a group of neo-fascists, while “Little Brother” depicts activist Frendon Blythe’s trial before an AI jury. Mosley’s approaches of cyberpunk emphasizes race and economic inequality alongside the genre’s traditional themes of social alienation and technological dominance.

Romance

This Is How You Lose the Time War - Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone (2019)

Red and Blue are time travelers from rival factions vying to shape the future according to mutually exclusive goals. The two women begin leaving each other secret notes throughout the timelines they traverse, evolving from enemies into lovers. Given their employer’s antagonistic relationship, Red and Blue must find subversive ways to resist the powers that be. Written through an authentic exchange of letters between the two authors, the book’s romance narrative is imbued with both emotional and thematic depth.

“Cozy” fiction

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet - Becky Chambers (2014)

Rosemary Harper leaves her home on Mars to join the crew of the Wayfarer, a space tunneling ship with a mixed-species crew. As the ship travels to a far-flung planet, each crew member’s past comes to the fore, and Rosemary must ultimately reveal her own secrets. Chambers’ debut novel is undoubtedly introspective and comforting but that doesn’t mean it’s shallow. Her characters are aren’t perfect but they consistently look for peaceful solutions and pursue acceptance even in tricky circumstances. Chambers’ future might not be utopian, but it might actually be one we want to live in.3

Humor

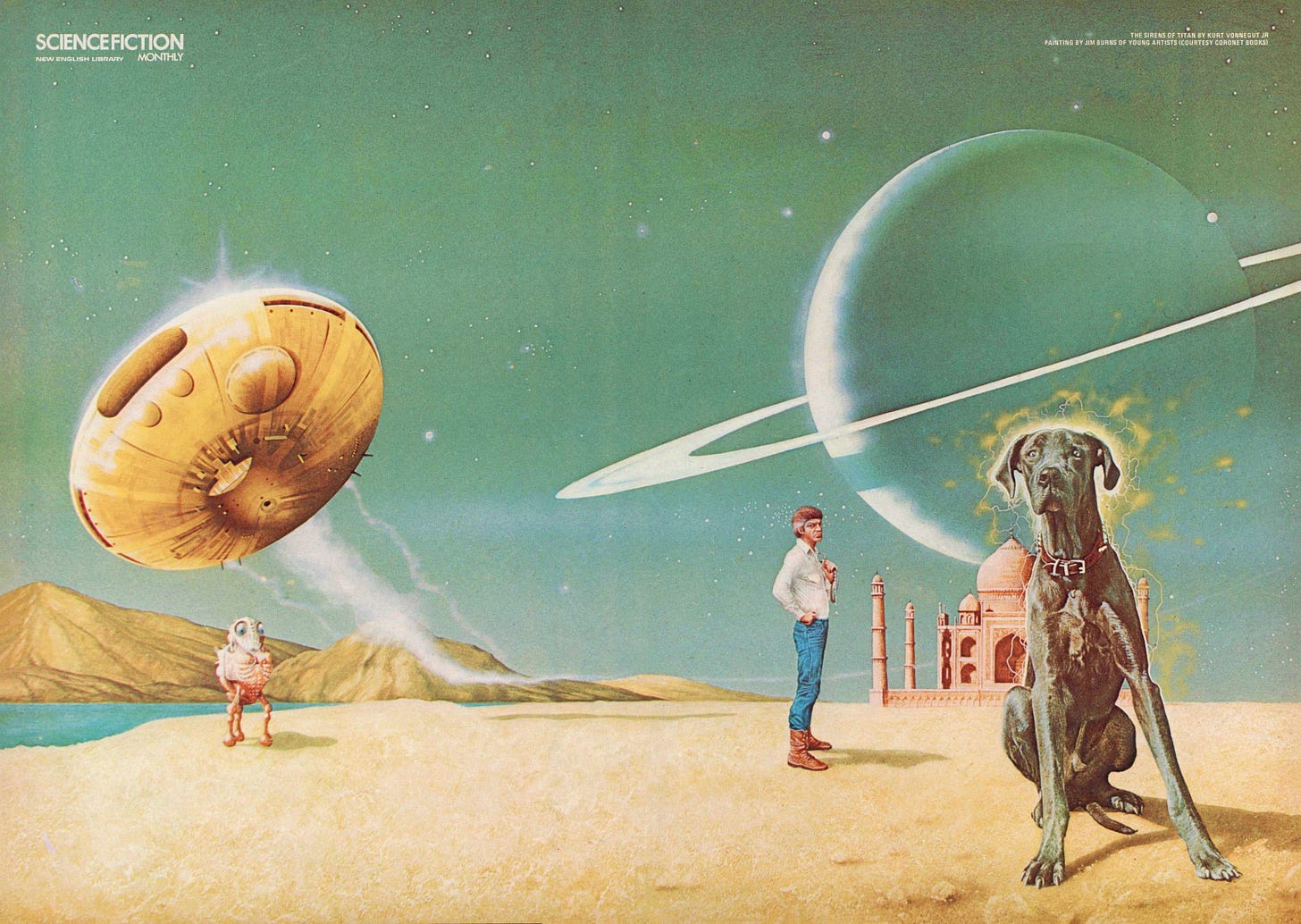

The Sirens of Titan - Kurt Vonnegut (1959)

Malachi Constant is the richest man in the world, a distinction he enjoys to the fullest and attributes to “divine favor”. After hearing a frightening prophecy of his own future, Constant uses his wealth to fund an interstellar journey that takes him to Venus, back to Earth, and eventually to Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. Along the way, Constant encounters a series of inconceivable situations that force him to reconsider both his and humanity’s place in the universe. Vonnegut is regarded as one of the great satirists in American literature, and in Sirens he achieves a tone that is equal parts sardonic and humanistic. By leaning into the outlandish side of science fiction, Vonnegut crafts a novel that is not just funny and profound, but profound because it’s funny. Like much of Vonnegut’s work, Sirens deals with notions of free will and omniscience.

Politics

The Dispossessed - Ursula K. LeGuin (1973)

Shevek is a physicist formulating a theory about the fundamental structure of time. Unable to complete his research due to manual labor obligations and the presence of rivals, Shevek journeys to the capitalist nation of A-Lo on the neighboring world of Urras. While the research environment proves much more fertile, Shevek must now ensure that his research is not co-opted by A-Lo’s government for nefarious ends. The Dispossessed deals heavily with political philosophy, exploring the implications of the capitalist, communist, and anarchist governments that appear throughout its narrative. The novel also deals with the relationship of science - both as a practice and a way of thinking - to politics and the state. Indeed, Le Guin modeled Shevek on J. Robert Oppenheimer, who was a friend to her parents.

Mars trilogy - Kim Stanley Robinson (1991-93)

In the early 21st century, the first humans settle on Mars and begin terraforming the planet shortly after. Almost immediately, Mars’ new inhabitants begin developing new philosophical, political, and scientific ideas, which are further developed by their native-born “Martian” children. Spanning nearly two centuries, the Mars trilogy chronicles the residents of the red planet as they navigate evolving political and economic relationships with Earth and contend with the social effects of new technological advancements. Kim Stanley Robinson’s novels are packed to the brim with detail, and his fully-drawn characters supplement the books’ complicated geopolitics with a distinct human element.

Philosophy

“The Truth of Fact, the Truth of Feeling” - Ted Chiang (2013)

Ted Chiang’s 2013 novelette follows twin narratives, one chronicling the introduction of writing to a Tiv tribe and the second a mock news article about technological advances granting users perfect memory. Though its premise is similar to a Black Mirror episode from two years earlier, Chiang’s story is much more nuanced, exploring empiricism, recurrent patterns in technological development, and the idea of memory itself rather than simply relying on emotional payoff.

Roadside Picnic - Arkady and Boris Strugatsky (1972)4

Aliens have visited Earth but without initiating any sort of first contact, littering several “Visitation Zones” across the planet with strange objects and physical anomalies instead. Red Schuhart is a “stalker” who makes his living by smuggling objects out of one such Zone for sale on the black market. After learning that his girlfriend Guta is pregnant, Schuhart struggles to get his act together, ultimately deciding to make one last trip into the Zone in search of the mythical wish-granting “Golden Sphere”. At the the core of the novel are questions of agency and self-determination, prompted by Red’s reliance on the incomprehensible Zone for the survival of his family.

If you want some history…

While some readers might just be looking for a new book to dig into, some of you might want to better understand the history and scope of science fiction. This section is for the latter group, and includes representative works from several periods in the history of science fiction.

The Time Machine - H.G. Wells (1895); link

Referred to as the “father of science fiction” or the “Shakespeare of science fiction”, H.G. Wells’ shaped the genre before it could properly be called one. In his 1895 novella The Time Machine, a Victorian scientist journeys hundreds of thousands of years into the future and recounts his encounters with two post-human races: the delicate Eloi and the brutish Morlocks. Wells was both a respected English literary figure and a futurist and through his science fiction he explored how humanity might progress technologically, politically and socially. His influence on science fiction is difficult to overstate and The Time Machine’s portrayal of humanity’s division into separate species remains a particularly enduring vision of the far future.

“The Comet” - W.E.B. DuBois (1920); link

Though he was best known as a pioneer of the Civil Rights Movement, W.E.B. DuBois nonetheless made an foundational contribution to science fiction while the genre was still in its infancy. “The Comet” follows Jim, a Black man living in New York City, who emerges from a job in a bank vault to find himself seemingly the sole survivor of a catastrophic impact. Driving around the city, he meets Julia, a wealthy young white woman who also survived the impact. Together, they must come to grips with the fact that they alone represent humanity’s future despite the racial divisions of their segregated society. “The Comet” established science fiction as a modality for discussing race, an issue not frequently taken up by other writers until decades later

“Shambleau” - C.L. Moore (1933); link

Despite the influence of literary luminaries like H.G. Wells, science fiction’s emergence as a distinct genre took place in the “pulps” - cheaply produced magazines known for publishing lowbrow genre stories. Catherine Lucille Moore was one of the first women to write science fiction for the pulps, and created the outlaw antihero Northwest Smith, who has drawn comparisons to Han Solo in recent years. In “Shambleau”, Smith rescues an attractive young woman from a angry mob on Mars and allows her to take refuge in his room. Increasingly captivated by her beauty, he soon realizes that she’s not quite human. Beyond being a canonical work of space opera, cosmic horror, and pulp SF in general, the story works as a legitimate allegory for addiction.

“Who Goes There” - Don A. Stuart (1938); link

While writers like Moore essentially wrote fantasy stories set in outer space, others sought to put the “science” in science fiction. John W. Campbell was one such author, known for including copious amounts of technical detail that reflected his hope to become an inventor5. Instead, Campbell became the editor of the pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction and arguably the most important individual in SF over the first half of the 20th century. His tenure as the editor of Astounding is referred to as the the “Golden Age of Science Fiction” accordingly. “Who Goes There” is Campbell’s signature work, published under the pen name Don A. Stuart shortly before his editorial duties forced him to quite writing stories himself. The story follows a group of scientists at an outpost in Antartica, who struggle to survive as a shapeshifting alien infiltrates their base. Adapted for the screen no fewer than three times6, the story’s atmosphere and characterization of distrust made it an influential work of both science fiction and horror.

Foundation series - Isaac Asimov (1942-50)

During his time at Astounding, Campbell helped launch the careers of a number of young science fiction writers who would become influential in their own right. Campbell’s influence was especially pronounced on a young Isaac Asimov, whose elaborate future history began with short stories published in Astounding during the 1940s. These early works introduced mathematician Hari Seldon and his theory of psychohistory - a science capable of predicting the actions of large populations. Foreseeing the fall of the current galactic empire, Seldon establishes the Foundation, a project to shorten the ensuing “dark age” predicted by psychohistory. Over the centuries, the Foundation must deal with unforeseen threats due to changes in technology, politics, and humanity itself. As science fiction novels gained popularity in the 1950s, Asimov’s stories were stitched together into a trilogy of fix-up novels, solidifying him as one of SF’s top writers. Decades later, Asimov’s exploration of how humanity might rationally forecast and even direct the future remains highly influential.

“Aye, and Gomorrah” - Samuel R. Delany (1967); link

The dominant form of SF remained largely unchanged throughout the rest of the ‘50s, marked by an emphasis on technical accuracy, linear storytelling, and a mostly uniform approach to both characterization and prose. These conventions were challenged in the ‘60s by a new generation of writers, many of whom were inspired by the countercultural movements of their day. Called the “New Wave”, this emerging brand science fiction saw increased exploration of taboo topics including sexuality and drug use, a stronger attention to social and philosophical issues, and a decreased emphasis on technical accuracy. In “Aye, and Gomorrah”, all astronauts are neutered before puberty to avoid the effects of space radiation on their offspring. These “Spacers” grow up into androgynous results who are shunned by mainstream society but fetishized by a subculture known as “frelks”. The story follows one unnamed Spacer as he experiences these dynamics firsthand in cities across Earth. Samuel R. Delany was one of the first gay and black writers in science fiction, and helped establish the genre as a place for the exploration of sexuality and social divisions.

Houston, Houston Do You Read? - James Tiptree, Jr. (1976)

The New Wave precipitated the emergence of other new SF subgenres, including one rooted in second-wave feminism. Among the most important writers of feminist SF was Alice Sheldon, who wrote under the male nom de plume James Tiptree, Jr. until 1977.7 Houston, Houston Do You Read? follows a group of astronauts who arrive back on Earth three hundred years after leaving, having sustained damage from a solar flare during their mission. They gradually realize that the planet they have returned to is not exactly what it seems. Though it deals with heady concepts such as alternative possibilities in gender relations and the construction of individual identity, the novella is one of Tiptree’s more approachable works, with a straightforward narrative and less experimental prose than many of her other stories.

Snow Crash - Neal Stephenson (1992)

The evolution of SF over the last third of the 20th century has been characterized less by overall shifts in the genre than the emergence of new schools or subgenres in parrallel. One of the most recognizable such movements is cyberpunk, a mixture of low life and high tech8 that emerged in response to the economic and technological developments of the 1980s. Many of the cyberpunk stories from this period are rather dense; I think a better starting point comes from the decade after.

Perhaps the most recognizable of these is cyberpunk, often described as a mixture of high tech and low culture. Although cyberpunk coalesced into a recognizable subgenre in the 1980s, I think the best starting point comes from the decade after. Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash is set in a future United States that has disintegrated into an agglomeration of corporate franchises. The story follows hacker Hiro Protagonist as he traverses the metaverse, searching for the origin of the computer virus that killed his best fried Da5id. Stephenson’s style is intentionally outlandish but Snow Crash reads like a breeze, replete with humor, action, and impressively parsable descriptions of Sumerian mythology.

Where not to start

Part of the reason that I’ve decided to create a list of starting places rather than simply of my favorite books is because I do believe that there are wonderful SF stories that might not be fun reads for people with less familiarity with the genre. In this section, I’ll provide some general characteristics of such stories alongside a few prominent examples.

Don’t start with works that are particularly dense or confusing.

Even if you’re well-versed in another dense style of literature (e.g., postmodernism), I believe it will likely be better to ease yourself into SF. This is primarily because in addition to difficulties arising from prose and narrative structure, dense SF novels are made difficult by confusing or even ambiguous descriptions of the technology and fantastic phenomena that characterize the genre. Getting a bit of practice reading about these things before jumping headlong into a difficult novel is highly recommended.

Examples: works by William Gibson (Neuromancer, The Peripheral, etc.), Book of the New Sun, Solaris, Dhalgren

Don’t start with works with lots of indirect exposition.

While many writers throughout the history of SF have relied on direct explanation to help readers understand their future worlds or alternative scenarios, other authors have relied simply on stating facts about these worlds in passing and counting on the reader to catch up. This technique is not exclusive to SF, but is frequently used within it, and the complexity of many SF settings makes it particularly difficult to get used to at first.

Examples: Dune, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, “The Girl Who Was Plugged In”

Don’t start with novels that rely on prior knowledge of SF history.

There are a number of SF works that might be viewed as “responses” to other works in the genre, or deconstruct elements of it. Thus, certain books are made more enjoyable by a knowledge of what came before, including the tropes and general history of science fiction. Sometimes such knowledge will merely provide the reader access to inside jokes, but frequently it is in fact crucial to unlocking core themes of the works.

Examples: Dune, 2001: A Space Odyssey, The Forever War

Eagle-eyed readers will notice that I abbreviate science fiction as “SF” rather than using a term like “sci-fi”. This type of terminology has been subject to debate for decades within the community; many fans who prefer SF deride “sci-fi” as a marketing term or a phrase indicative of low quality. I’ve gotten in the habit of using SF so as not to run afoul of those who dislike the term, even though I personally have no such issue with it. That would, after all, take time away from more important topics - namely, the books themselves!

Briefly, this means that the Earth is flat and that the Sun and Moon revolve around it. Heaven is directly above the sky, separated by barrier known as a “firmament”. See this page for a helpful visual schematic.

This last phrase is lifted from Chambers herself in this wonderful discussion from the Long Now Foundation. The notion of optimism in SF deserves its own post, but suffice it to say that I find myself quite aligned with Chambers’ philosophy of how to imagine the future.

Prospective readers should that the novel has two different English translations: Antonina Bouis’ 1977 interpretation was based on the version of the novel approved by Soviet censors, while Olena Bormashenko’s 2012 effort derived from the original uncut manuscript.

The history in this section is drawn from Astounding, Alec Nevala-Lee’s group biography on Campbell and several other important Golden Age SF writers.

As The Thing From Another World in 1951 and The Thing in 1982 and 2011.

Ursula K. LeGuin’s introduction to the Tiptree collection Star Songs of an Old Primate provides an interesting account of this revelation’s effect on the SF community.

This phrase has become a rather ubiquitous description of cyberpunk, but as far as I can tell it comes from Bruce Sterling’s preface to William Gibson’s collection Burning Chrome.